Just one year after completing my PhD thesis on law firm pro bono and access to justice, and nearly five years after first starting work as a pro bono manager, I am incredibly excited to have been appointed to the board of the Association of Pro Bono Counsel (APBCo). APBCo, is the US-based mission-driven membership organization of over 200 attorneys who run pro bono practices in over 100 of the world’s largest law firms.

I will be only the second non-US member of APBCo to be appointed to the board, and the first that is based in Continental Europe. And so, to mark the occasion, I wanted to share a few reflections on the state of Big Law pro bono in Europe (as compared with the United States).

Big Law Pro Bono in the United States: Filling the Justice Gap

“Pro bono”, the provision of free legal services to persons in need, is a practice as old as the legal profession itself. You can find examples of pro bono as far back as Ancient Athens and Republican Rome. Throughout much of both European and American history, pro bono legal services were provided sporadically, either by individual lawyers acting by themselves or in a semi-organized manner (e.g. by religious organizations, law schools, bar organizations, municipalities or civil society groups) typically out of a sense of charity.

However, the practice of “Big Law” pro bono (i.e. lawyers at large elite law firm providing free legal services to promote the public interest) is relatively new. It first emerged in the United States in the 1960s during President Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” The “Poverty Law Movement” sought to, “marshal the forces of law and the strength of lawyers to combat the causes and effects of poverty”. Through the Poverty Law Movement, pro bono was transformed from a sporadic form of legal charity to an organized focus on “access to justice”— targeting direct legal services for the poor.

Today in the US, pro bono accounts for between one quarter and one third of civil legal aid provided in the United States. It has even been suggested that, pro bono is the “dominant means of dispensing free representation to poor and underserved clients, eclipsing state-sponsored legal services and other nongovernmental mechanisms in importance”. How did this happen?

1. Active lobbying by students and civil society: Firstly, during the 1970s, elite law students and legal aid organizations (e.g. the National Legal Aid and Defender Association) actively lobbied law firms to set up pro bono programs focused on providing free legal services to the poor.

2. Decline in funding and scope of federal legal aid: Secondly, between the 1970s (under the Nixon administration) and the 1990s (through the Regan and Bush administrations) funding of the federal legal services program (i.e. federal funding for civil legal aid) was decimated. This created an “access to justice movement” with many lawyers, legal scholars and even politicians calling for Big Law pro bono to fill the justice gap.

3. Pressure from the organized Bar: Thirdly, in 1993, the American Bar Association (ABA), introduced a model rule establishing an aspirational target of 50 hours of pro bono for ALL lawyers (a “substantial majority” of which needed to be targeted to “persons of limited means”).

The consequence of all this, was that Big Law pro bono in the United States came to be understood functionally as one solution to the “justice gap”, i.e. as a resource oriented toward the provision of civil legal aid for low-income individuals. This includes helping persons in need with a wide range of legal issues from housing rights and voting rights to immigration law issues. Between the 1970s and the present day, America’s largest law firms began to adopt pro bono policies, establish pro bono committees and appoint full-time pro bono managers. Today, you will find full-time pro bono managers, and sometimes even entire departments, mandated to run law firm pro bono programs at each and every one of the top 100 or so US law firms.

Big Law Pro Bono in Europe: In Pursuit of Human Rights?

What about Big Law pro bono in Europe? Can we confidently say that it promotes access to justice like its US ancestor? The short answer is no, in Europe, Big Law pro bono does not significantly contribute directly to access to justice for the poor (more on that later). Rather, Big Law pro bono in Europe has taken a unique shapeand is oriented towards providing legal assistance to Europe’s large population of non-governmental organizations and civil society organizations, especially those organizations focused on human rights advocacy.

Despite Europe having a very long history of pro bono in general, Big Law pro bono is a very recent phenomenon. How did Big Law pro bono come to exist in Europe? Between the 1980s and the early 2000s, the largest US firms (and several large London firms) began to establish “foreign offices” in capital cities across Continental Europe. As firms expanded globally, they took their pro bono programs with them. In the words of one US Pro Bono Counsel, (talking in 2003), “our commitment to pro bono is global in nature…one firm, one commitment, one policy.” Talking in 2015, she put it another way, “there is legal need in all jurisdictions, so to require pro bono in the US but not in Kazakhstan does not hold water.” As each firm established new overseas offices in Europe, pro bono managers (typically based in New York, D.C. or Chicago) began to wonder how to engage overseas (Continental European) lawyers in pro bono also.

Critically, Big Law pro bono in Europe did not emerge in response to a specific legal need (as with the US Poverty Law and Access to Justice Movements). Rather, it was a byproduct of large law firm globalization. It was a resource in search of demand. Unlike in the US, demand came not in the form of the legal needs of the poor. Rather, it came in the form of legal needs from non-profit organizations. Indeed, today, likely around 85% of the pro bono work carried out by large law firms in Europe is targeted at non-profits, and only a very small fraction is targeted at the legal needs of poor individuals. Why?

Much of the answer is down to historical contingency. In the 1970s, the International Human Rights Movement reached its zenith in Europe (in particular in Central and Eastern Europe under socialist rule). Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, scores of human rights organizations were established by former political dissidents. Throughout the 1990s, thanks in part to the efforts of philanthropic foundations such as the Ford Foundation and the Open Society Foundations, these organizations began to focus their efforts on legal advocacy – using law as a tool to promote social justice in the new democracies of Central and Eastern Europe. The Polish Helsinki Foundation is a terrific example, but there are many, many more. This population of non-profits and the international NGOs that worked with them (Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch etc.) initially became the primary pro bono clients of large law firms in Europe. These organizations had very substantial legal needs (especially for comparative law) as they sought to enforce International and European human rights standards domestically (and through the European Court of Human Rights). Large law firms could undertake comparative legal research projects that non-profits would be unable to afford on the open market.

When the US and London-based pro bono managers began looking for pro bono work for their European lawyers in the early 2000s, it was Europe’s population of human rights organizations (especially those focused on legal advocacy) that they first turned to. This came about fortuitously through overlapping networks between progressive lawyer circles in the US and Europe.

However, this is not the only reason that Big Law pro bono in Europe is focused primarily supporting non-profits. There are several others. One of the most important is the role played by the “Social Bar” in Europe. Since the early 2000s essentially every European country has an organized legal aid system, providing state funded or subsidized free legal services to the poor. These legal aid systems are extremely well funded in some countries (e.g. the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway) and not very well funded in others. The result of state-funded legal aid programs, in many parts of Europe, has been the emergence of what might be referred to as a “Social Bar” – lawyers working in private practice who specialize in areas of law typically relevant to the problems of the poor and whose work is subsidized by the state. Such lawyers develop practices that concentrate around, family law, immigration law, criminal law, employment and housing. In some countries, such as France and the Netherlands, the social Bar represents nearly 50% of the entire legal profession (counting tens of thousands of lawyers). With such significant numbers of specialized lawyers funded by the state to address the legal needs of the poor, there is less of a clear role for corporate lawyers (at large firms) to play in addressing these issues.

Big Law Pro Bono in Europe Today

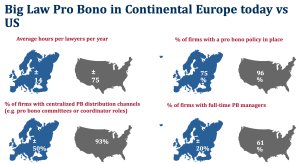

Key figures:

4500 = approx. # of lawyers doing pro bono among the top 30 firms (=120 FTE)

14 = # of hours per lawyer per year of PB across all lawyers at top 30 firms (=47 hours per year among those lawyers actually doing pro bono)

200,000 = approx. total # pro bono hours among top 30 firms per year (= approx. 85 million Euros per year)

15% = percentage of pro bono work carried out for needy individuals vs. 85% for non-profits

Key facts:

· CCBE (European Bar) has no authority to generate pan-European standards on pro bono (like the ABA) – only the national Bars can do so.

· Firms rely significantly on national clearinghouses (there is at least one in virtually every EU country dedicated to connecting pro bono demand with pro bono supply) to source pro bono matters. The clearinghouses focus primarily on serving national non-profit organizations.

Does Big Law Pro Bono in Europe Contribute to Access to Justice?

If we define access to justice, as it is commonly defined, in terms of access of legal services (i.e. as fundamentally concerned with providing no-cost or low-cost services to expand the entry of the poor into the legal system on an individual, case-by-case basis), then we must conclude that Big Law pro bono in Europe is not primarily concerned with access to justice. As mentioned, likely less than 15% of Big Law Pro Bono work involves providing legal services directly to individuals in Europe. Among the top 30 commercial law firms, this might amount to less than 20 full time equivalent lawyers working on pro bono over one year. When you consider that there are approximately 8000 legal aid lawyers in the Netherlands, 4000 in Belgium, 25,000 in France and even 139 civil legal aid lawyers in Latvia, we must conclude that Big Law Pro Bono makes a very limited contribution to access to justice defined in this way.

So, what is the social value of Big Law pro bono in Europe, if not related to access to justice?

1. Corporate support: Firstly, a significant amount of Big Law pro bono work in Europe involves the provision of “corporate support” i.e. legal assistance provided to non-profits as incorporated legal entities, relating to their legal structure and governance, employment practices, tax obligations, financing, intellectual and real property rights, commercial transactions and so on. Although there are no reliable statistics, it is likely that such work makes up a significant proportion of the pro bono work being carried out by large firms across Europe. A legal needs survey I carried out among 100 European non-profits revealed that 63% of the surveyed organizations expressed a need for pro bono support in relation to governance and corporate legal issues, while 61% expressed a need for support with employment issues, 53% with tax and 43% each with respect to data protection and intellectual property issues.

2. Supporting legal and policy advocacy: In the last fifty or so years, the supranational European Union (EU) governance structure and its major institutions have become immensely powerful. They now play a big role in shaping the everyday experience of living in Europe. The rising power and importance of the EU institutions have also given rise to an expansion of financed lobbying activity in Brussels. From tobacco companies and food manufactures to airlines and banks, Big Business is now very keen to have the ear of the EU institutions and is not afraid to invest vast sums of money to ensure favorable policy outcomes. Moreover, the EU legislative, judicial and policy landscape in Europe is immensely sophisticated. It is characterized by vertical plurality (i.e. the overlap and interaction between local, national, European and international norms and norm-generating bodies), horizontal plurality (i.e. the growing relevance of norms generated in all parts of Europe right across Europe: so that norms generated in Hungary or Sweden can be significant in Latvia or Italy) and intense complexity, such that there are simultaneously multiple avenues for engaging in the legislative, judicial and policy processes (litigation, administrative actions, consultations, petitions, etc.) and significant specialization within various fields (environmental law, asylum law, discrimination, labor and social law, free movement law, etc.). For non-profits and civil society organizations this landscape makes it all the more important to engage. Firstly, such powerful institutions can have dramatic effects on society, for better or worse. Secondly, reforms and policy changes in one part of the system can have an impact across the whole system, making the stakes of engagement much higher. However, engagement is also rendered much more difficult. Significant sophistication is required to engage effectively both in terms of access to comparative legal and policy knowledge and in terms of specialized knowledge or expertise in relation to the various avenues of participation and substantive bodies of law and policy. In this context, Big Law pro bono plays an important role by facilitating non-profits to effectively engage in the legislative, judicial and policy processes. Without access to specialized and comparative legal expertise and knowledge, non-profits simply cannot effectively engage and with limited budgets, they often simply do not have access to such resources. Moreover, European non-profits rarely have sufficient legal staff in-house. A survey I carried out among 100 EU policy NGOs revealed that just 32% of them had lawyers on-staff (50% of those with just 1 lawyer) and several of those lawyers were either exclusively or additionally handling compliance and operational or corporate matters rather than contributing to advocacy campaigns and programmatic work. Meanwhile, in comparison, a 2004 survey among around 300 public interest NGOs in the US revealed that over 50% of them had more than 5 lawyers on staff (40% having ten or more lawyers on staff).

3. Strategic Litigation: Big Law pro bono in Europe also plays a small but growing role in non-profit-led strategic litigation campaigns. I.e. carefully planned, long term, litigation campaigns pursuing public interest causes. A recent example in this vein relates to the Coman case recently decided by the Court of Justice. The Romanian LGBTi advocacy group Accept teamed up with an international law firm to achieve an important legal judgment at the European Court of Justice in 2017. A team comprised of experienced corporate commercial litigators and Romanian human rights lawyers persuaded the Grand Chamber of Court of Justice to hold that the term “spouse” includes same sex spouses of EU citizens for the purpose of freedom of movement and residency rights in the EU. Such case examples of commercial law firms playing a role in these kinds of cases are rare but are becoming increasingly less so. At my own firm, particularly in our Central and Eastern European offices, there is a steady stream of such cases (related to anti-discrimination law and freedom of expression in particular) underway at any given time.

Ultimately then, Big Law pro bono in Europe, while not yet oriented towards access to justice for low income individuals, is of great benefit to the many civil society organizations (and especially human rights organizations) that blossomed, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Critically, Big law pro bono in Europe fills the large demand for legal services among Europe’s diverse population of non-profit organizations.